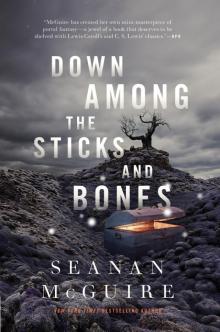

Read Down Among the Sticks and Bones Online Free

Begin Reading

Tabular array of Contents

Most the Author

Copyright Folio

Cheers for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For electronic mail updates on the writer, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you lot without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied then that you can enjoy reading information technology on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal apply only. You may not print or post this eastward-book, or make this east-book publicly available in any way. You may non re-create, reproduce, or upload this due east-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the police force. If you believe the copy of this eastward-book y'all are reading infringes on the author's copyright, please notify the publisher at: usa.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR One thousand thousand

I think the rules were different in that location. It was all about science, only the science was magical. It didn't intendance about whether something could be done. It was about whether it should be washed, and the answer was always, e'er yes.

—JACK WOLCOTT

Role I

JACK AND JILL LIVE UP THE Loma

1

THE Dangerous Allure OF OTHER PEOPLE'South CHILDREN

PEOPLE WHO KNEW Chester and Serena Wolcott socially would accept placed coin on the idea that the couple would never choose to have children. They were not the parenting kind, past any reasonable interpretation. Chester enjoyed silence and solitude when he was working in his habitation office, and viewed the slightest departure from routine as an enormous, unforgiveable disruption. Children would be more than a slight deviation from routine. Children would exist the nuclear option where routine was concerned. Serena enjoyed gardening and sitting on the lath of various tidy, elegant nonprofits, and paying other people to maintain her home in a spotless state. Children were messes walking. They were trampled petunias and baseballs through picture windows, and they had no identify in the advisedly ordered globe the Wolcotts inhabited.

What those people didn't meet was the fashion the partners at Chester's law firm brought their sons to piece of work, handsome little clones of their fathers in historic period-appropriate menswear, hereafter kings of the world in their perfectly shined shoes, with their perfectly modulated voices. He watched, increasingly envious, equally junior partners brought in pictures of their own sleeping sons and were lauded, and for what? Reproducing! Something and so elementary that whatever beast in the field could do information technology.

At nighttime, he started dreaming of perfectly polite little boys with his hair and Serena's eyes, their blazers buttoned just so, the partners beaming beneficently at this proof of what a family unit human he was.

What those people didn't come across was the way some of the women on Serena'south boards would occasionally bring their daughters with them, making apologies nigh incompetent nannies or unwell babysitters, all while secretly gloating equally everyone rushed to ooh and ahh over their cute babe girls. They were a garden in their own right, those privileged daughters in their gowns of lace and taffeta, and they would spend meetings and tea parties playing peacefully on the edge of the carpeting, cuddling their stuffed toys and feeding imaginary cookies to their dollies. Everyone she knew was quick to compliment those women for their sacrifices, and for what? Having a baby! Something so easy that people had been doing it since time began.

At night, she started dreaming of beautifully composed trivial girls with her rima oris and Chester's nose, their dresses explosions of fripperies and frills, the ladies falling over themselves to exist the showtime to tell her how wonderful her daughter was.

This, you lot run into, is the true danger of children: they are ambushes, each and every one of them. A person may expect at someone else's child and see only the surface, the shiny shoes or the perfect curls. They do non come across the tears and the tantrums, the late nights, the sleepless hours, the worry. They do non even see the love, not really. Information technology can be piece of cake, when looking at children from the outside, to believe that they are things, dolls designed and programmed by their parents to deport in one manner, following ane set of rules. It tin be piece of cake, when standing on the lofty shores of adulthood, not to remember that every developed was in one case a child, with ideas and ambitions of their ain.

It can be easy, in the end, to forget that children are people, and that people volition do what people will do, the consequences be damned.

It was right later on Christmas—circular after round of interminable office parties and charity events—when Chester turned to Serena and said, "I have something I would like to talk over with you lot."

"I desire to have a babe," she replied.

Chester paused. He was an orderly man with an orderly wife, living in an ordinary, orderly life. He wasn't used to her beingness quite then open with her desires or, indeed, having desires at all. It was dismaying … and a trifle exciting, if he were existence honest.

Finally, he smiled, and said, "That was what I wanted to talk to you about."

There are people in this world—good, honest, hard-working people—who desire zippo more than to have a baby, and who effort for years to excogitate one without the slightest success. There are people who must see doctors in pocket-size, sterile rooms, hearing terrifying proclamations about how much information technology will price to even begin hoping. At that place are people who must go on quests, chasing down the north wind to inquire for directions to the Business firm of the Moon, where wishes can be granted, if the hour is correct and the need is great enough. There are people who will endeavour, and try, and endeavor, and receive naught for their efforts only a broken heart.

Chester and Serena went upstairs to their room, to the bed they shared, and Chester did non put on a rubber, and Serena did not remind him, and that was that. The side by side morning, she stopped taking her nascency control pills. Three weeks later, she missed her menstruum, which had been as orderly and on-time as the rest of her life since she was twelve years old. Two weeks after that, she sat in a small white room while a kindly man in a long white glaze told her that she was going to be a female parent.

"How long before we tin can get a film of the babe?" asked Chester, already imagining himself showing it to the men at the function, jaw potent, gaze distant, like he was lost in dreams of playing catch with his son-to-be.

"Yep, how long?" asked Serena. The women she worked with always shrieked and fawned when someone arrived with a new sonogram to pass around the group. How prissy information technology would exist, to finally be the center of attending!

The doctor, who had dealt with his share of eager parents, smiled. "Yous're well-nigh five weeks forth," he said. "I don't recommend an ultrasound before twelve weeks, nether normal circumstances. Now, this is your first pregnancy. Yous may want to wait before telling anyone that you're meaning. Everything seems normal now, simply it'due south early days yet, and it will be easier if you don't have to take back an announcement."

Serena looked bemused. Chester fumed. To even advise that his wife might be then bad at being significant—something so simple that any fool off the street could practice it—was offensive in means he didn't fifty-fifty have words for. Just Dr. Tozer had been recommended by one of the partners at his firm, with a knowing twinkle in his eye, and Chester simply couldn't see a way to change doctors without offending someone also important to offend.

"Twelve weeks, then," said Chester. "What do we do until then?"

Dr. Tozer told them. Vitamins and nutrition and reading, so much reading. It was like the human being expected their infant to be the most hard in the history of the globe, with all the reading that he assigned. Merely they

did it, dutifully, like they were post-obit the steps of a magical spell that would summon the perfect child straight into their arms. They never discussed whether they were hoping for a boy or a girl; both of them knew, then completely, what they were going to have that it seemed unnecessary. And then Chester went to bed each night dreaming of his son, while Serena dreamt of her daughter, and for a time, they both believed that parenthood was perfect.

They didn't listen to Dr. Tozer's advice about keeping the pregnancy a secret, of class. When something was this good, it needed to be shared. Their friends, who had never seen them as the parenting type, were confused simply supportive. Their colleagues, who didn't know them well enough to understand what a bad thought this was, were enthusiastic. Chester and Serena shook their heads and made lofty comments about learning who their "real" friends were.

Serena went to her board meetings and smiled contently every bit the other women told her that she was beautiful, that she was glowing, that motherhood "suited her."

Chester went to his office and plant that several of the partners were dropping by "just to chat" almost his impending fatherhood, offering advice, offering camaraderie.

Everything was perfect.

They went to their starting time ultrasound engagement together, and Serena held Chester's paw as the technician rubbed blueish slime over her belly and rolled the wand across it. The picture began developing. For the first fourth dimension, Serena felt a pang of concern. What if there was something wrong with the infant? What if Dr. Tozer had been correct, and the pregnancy should have remained a secret, at least for a trivial while?

"Well?" asked Chester.

"You wanted to know the babe'southward gender, yes?" asked the technician.

He nodded.

"You accept a perfect infant girl," said the technician.

Serena laughed in vindicated delight, the sound dying when she saw the scowl on Chester'southward face. All of a sudden, the things they hadn't discussed seemed large plenty to fill up the room.

The technician gasped. "I have a second heartbeat," she said.

They both turned to look at her.

"Twins," she said.

"Is the second babe a boy or a daughter?" asked Chester.

The technician hesitated. "The first infant is blocking our view," she hedged. "Information technology's difficult to say for sure—"

"Gauge," said Chester.

"I'm afraid it would not be ethical for me to guess at this stage," said the technician. "I'll make you another appointment, for two weeks from now. Babies move around in the womb. We should be able to go a meliorate view then."

They did not get a better view. The outset baby remained stubbornly in forepart, and the 2d baby remained stubbornly in back, and the Wolcotts made information technology all the mode to the delivery room—for a scheduled induction, of form, the engagement chosen past mutual agreement and circled in their 24-hour interval planners—hoping quietly that they were about to become the proud parents of both son and daughter, completing their nuclear family on the first try. Both of them were slightly smug about the thought. It smacked of efficiency, of tailoring the perfect solution right out the gate.

(The thought that babies would become children, and children would become people, never occurred to them. The concept that perhaps biology was not destiny, and that not all little girls would exist pretty princesses, and non all little boys would be brave soldiers, too never occurred to them. Things might have been easier if those ideas had ever slithered into their heads, unwanted just undeniably important. Alas, their minds were made up, and left no room for such revolutionary opinions.)

The labor took longer than planned. Serena did not desire a C-section if she could help information technology, did not want the scarring and the mess, and so she pushed when she was told to push button, and rested when she was told to rest, and gave nativity to her first kid at five minutes to midnight on September fifteenth. The doctor passed the baby to a waiting nurse, announced, "It's a girl," and bent dorsum over his patient.

Chester, who had been holding out hope that the reticent male child-kid would push his fashion forrad and claim the vaunted position of firstborn, said aught as he held his wife'southward mitt and listened to her straining to expel their 2d child. Her face was blood-red, and the sounds she was making were zip brusk of animal. It was horrifying. He couldn't imagine a circumstance under which he would bear on her e'er again. No; it was good that they were having both their children at once. This way, information technology would exist over and done with.

A slap; a wail; and the doctor'south phonation proudly proclaiming, "Information technology's another healthy babe daughter!"

Serena fainted.

Chester envied her.

* * *

Afterward, WHEN SERENA WAS tucked safety in her individual room with Chester beside her and the nurses asked if they wanted to meet their daughters, they said yep, of class. How could they have said anything unlike? They were parents at present, and parenthood came with expectations. Parenthood came with rules. If they failed to see those expectations, they would be labeled unfit in the eyes of everyone they knew, and the consequences of that, well …

They were unthinkable.

The nurses returned with two pink-faced, hairless things that looked more like grubs or goblins than anything homo. "One for each of yous," twinkled a nurse, and handed Chester a tight-swaddled baby similar it was the most ordinary affair in the world.

"Have you idea well-nigh names?" asked another, handing Serena the second infant.

"My mother'due south name was Jacqueline," said Serena charily, glancing at Chester. They had discussed names, naturally, i for a girl, one for a male child. They had never considered the need to proper name two girls.

"Our head partner'due south wife is named Jillian," said Chester. He could claim it was his female parent's name if he needed to. No one would know. No 1 would ever know.

"Jack and Jill," said the offset nurse, with a smile. "Cute."

"Jacqueline and Jillian," corrected Chester frostily. "No daughter of mine will get past something as base and undignified as a nickname."

The nurse's smile faded. "Of grade non," she said, when what she really meant was "of class they will," and "yous'll see soon enough."

Serena and Chester Wolcott had fallen prey to the dangerous allure of other people'south children. They would acquire the fault of their ways soon enough. People similar them always did.

ii

PRACTICALLY PERFECT IN Virtually NO WAYS

THE WOLCOTTS LIVED in a house at the top of a loma in the heart of a fashionable neighborhood where every house looked alike. The homeowner's clan allowed for three colors of outside paint (ii colors too many, in the minds of many of the residents), a strict variety of fence and hedge styles around the front lawn, and modest, relatively quiet dogs from a very brusque listing of breeds. Most residents elected not to accept dogs, rather than deal with the complicated process of filling out the permits and applications required to own i.

All of this conformity was designed non to strangle just to comfort, assuasive the people who lived there to relax into a perfectly ordered earth. At night, the air was quiet. Condom. Secure.

Salvage, of course, for the Wolcott home, where the silence was split by good for you wails from two sets of developing lungs. Serena sat in the dining room, staring blankly at the 2 screaming babies.

"Y'all've had a bottle," she informed them. "Y'all've been changed. You've been walked around the house while I bounced y'all and sang that dreadful vocal about the spider. Why are you however crying?"

Jacqueline and Jillian, who were crying for some of the many reasons that babies cry—they were cold, they were distressed, they were offended by the existence of gravity—continued to wail. Serena stared at them in dismay. No 1 had told her that babies would cry all the fourth dimension. Oh, at that place had been comments most it in the books she'd read, just she had causeless that they were simply referring to bad parents who failed to take a properly business firm hand with their offspring.

"Can't you close them up?" demanded Chester from b

ehind her. She didn't accept to turn to know that he was standing in the doorway in his dressing gown, scowling at all three of them—as if information technology were somehow her error that babies seemed designed to scream without cease! He had been complicit in the creation of their daughters, but now that they were here, he wanted almost nothing to do with them.

"I've been trying," she said. "I don't know what they want, and they can't tell me. I don't … I don't know what to practice."

Chester had not slept properly in three days. He was starting to fearfulness the moment when information technology would impact his work and catch the attention of the partners, painting him and his parenting abilities in a poor light. Perhaps it was agony, or perhaps it was a moment of rare and impossible clarity.

"I'm calling my mother," he said.

Chester Wolcott was the youngest of three children: by the time he had come up along, the mistakes had been made, the lessons had been learned, and his parents had been comfortable with the process of parenting. His mother was an unforgivably soppy, impractical woman, but she knew how to burp a infant, and perchance by inviting her now, while Jacqueline and Jillian were likewise immature to be influenced by her ideas well-nigh the world, they could avoid inviting her after, when she might actually exercise some damage.

Serena would ordinarily have objected to the thought of her mother-in-law invading her home, setting everything out of club. With the babies screaming and the business firm already in disarray, all she could practice was nod.

Chester made the call start thing in the forenoon.

Louise Wolcott arrived on the train viii hours afterward.

By the standards of anyone save for her ruthlessly regimented son, Louise was a disciplined, orderly woman. She liked the world to brand sense and follow the rules. By the standards of her son, she was a hopeless dreamer. She thought the world was capable of kindness; she thought people were essentially good and but waiting for an opportunity to bear witness it.

Source: https://onlinereadfreenovel.com/seanan-mcguire/54024-down_among_the_sticks_and_bones.html

0 Response to "Read Down Among the Sticks and Bones Online Free"

Postar um comentário